5.4 Crime Victims and Media Treatment

Figure 5.7

While this topic has as its primary focus the nature of interactions between crime victims and the various media outlets which report crime stories, it largely concerns the impacts of journalistic mistreatment of crime victims. Whether intentionally inflicted or otherwise, crime victims may suffer additional harm due to these interactions, which can include on-screen interviews, photojournalism, or verbal communications on the radio. In some cases, more severe and prolonged harm can arise from these interactions than was first experienced in the initial criminal victimization. The unfortunate truth of this is, the media may have neither anticipated nor intended these consequences when fulfilling their crime reporting mission (Garcia, 2018; Justice Solutions, n.d.). They also may be completely unaware that they have inflicted any abuse, or that the abuse is continuing to occur. In this examination of victimization as a result of the treatment of the media, the practices of “sensationalism” and “tabloidism” are recognized. These practices create an environment of harm to crime victims and their families, especially when they cover crimes committed locally, or when describing highly-publicized crimes.

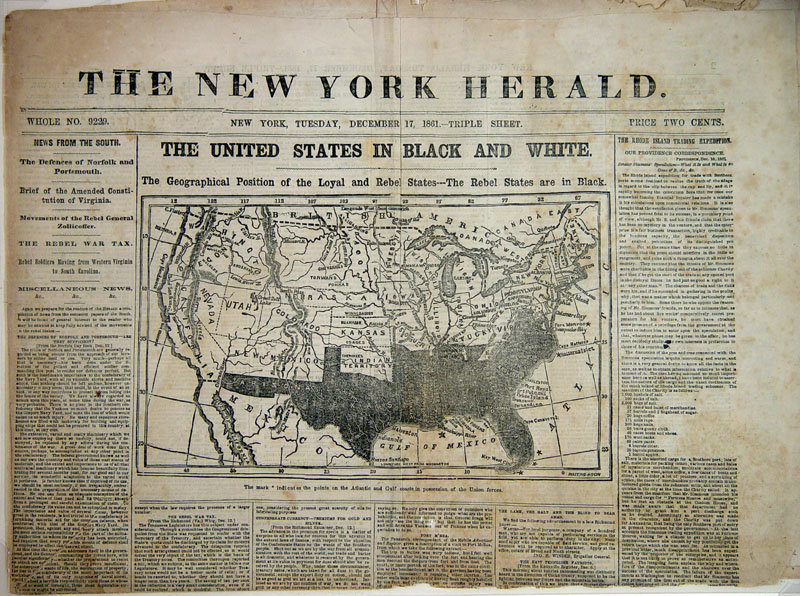

Figure 5.8

Picture of the New York Herald Penny Press

In the early years of journalism, the primary means of information communication was by newspapers and magazines.

The newspaper was the perfect medium for the increasingly urbanized Americans of the 19th century, who could no longer get their local news merely through gossip and word of mouth. These Americans were living in unfamiliar territory, and newspapers and other media helped them negotiate the rapidly changing world. (University of Minnesota Libraries, 1.3 section, para. 10)

The delay between the crime being committed, and when it was reported, created three advantages: 1) more time for investigation to occur, 2) more time for victim services (primitive as they may have been) to have taken place, and 3) a better chance that the original reporting would be correct.

This picture has changed dramatically with the onset of televised reporting, motion picture films (primarily documentaries, as well as productions based on fact), and social media.

Today, a media coverage of a crime can be captured in presentable format in literally seconds, if not in real time. Some years ago, media coverage by helicopter was criticized and finally subjected to strict guidelines (Federal Aviation Administration, 2016), due to the propensity of pilots flying over crime scenes, using telephoto lenses to capture movements and tactics, which could inform criminals of the presence and location of police seeking to apprehend them. Today’s journalists take a different approach, by attempting to get as close to the “action” as possible. This often leads to the police needing to deploy officers or other departmental employees to redirect or “stage” the media representatives out of harm’s way. Finally, in attempts to capture the “human interest” angle of criminal events, witnesses and sometimes victims themselves are interviewed nearly immediately after a crime has occurred, and sometimes before the victim has had an opportunity to mentally process what has happened. Taking an approach to quickly interview victims before all the facts are in and the victim, and others, have time to process what has happened, often does a disservice to persons dealing with the impacts of crimes.

Review Check