1.5 Criminal Justice Process

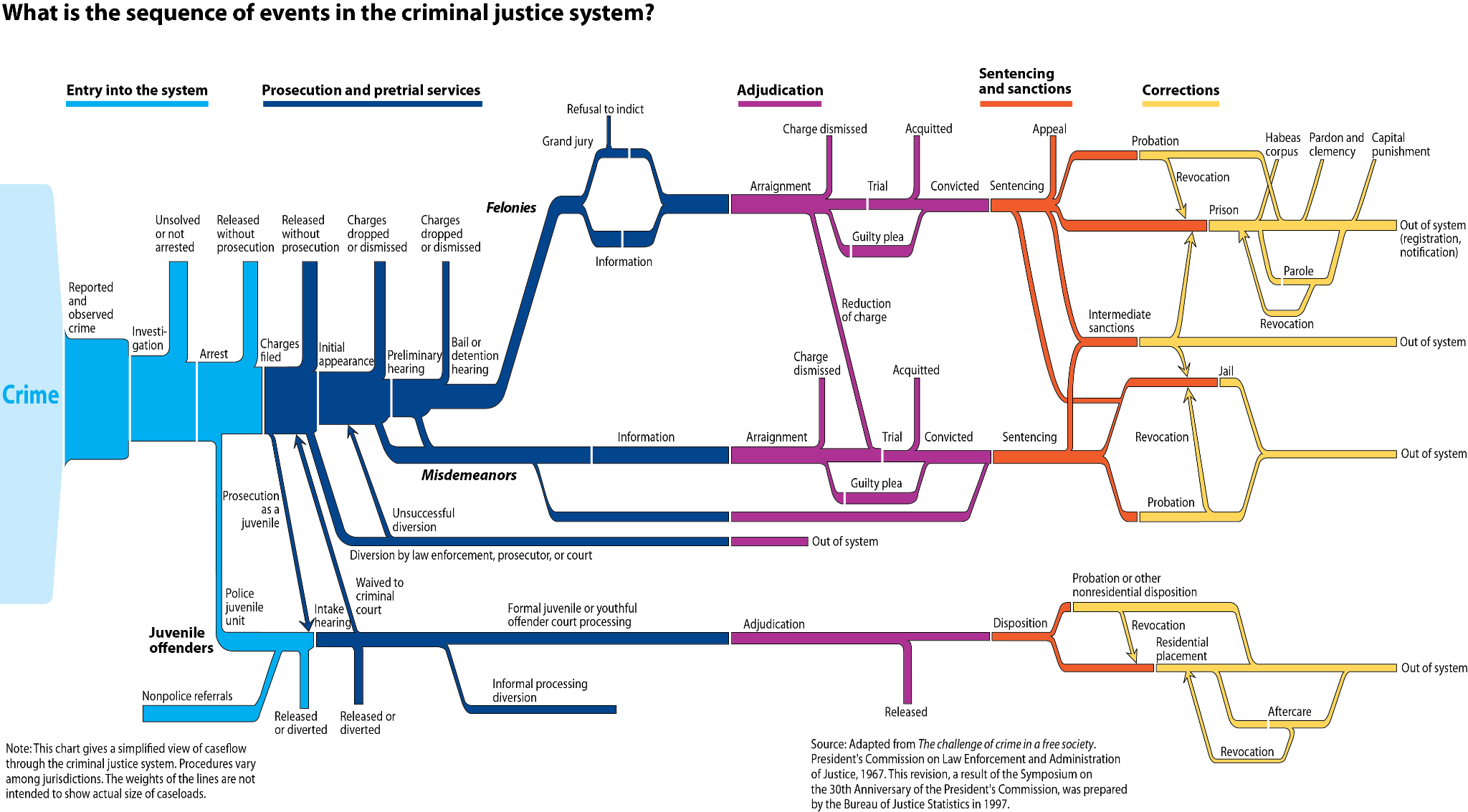

As a result of the variations in criminal justice system procedures across various states and the federal government, there exists no singular method for preceding through the criminal justice system. Regardless of nuance in the criminal justice process across different states and the federal government criminal justice systems, they all adhere to the guidelines set forth in the U.S Constitution regarding the fair and unbiased treatment of the accused throughout the criminal justice process (Bureau of Justice Statistics, 2021). Figure 1.8 below illustrates how individuals are processed into and move through the criminal justice system. Although this flowchart does not represent all criminal justice systems, it is a visual depiction intended to enhance the understanding of the general criminal justice process.

Figure 1.8

1.5.1 Crime Detection

The formal criminal justice process initiates with the detection of a law violation. Detecting law violators is a dynamic task that requires a blend of traditional investigative techniques, technological advancements, and community engagement (Braga et al., 2014). While law enforcement officials bear the formal responsibility for detecting law violations and criminal activity, the public also plays a significant role in crime detection and other phases of the criminal justice process. Instances of individuals engaging in suspicious or illegal activity may be observed either directly by a police officer or by a member of the public, who then reports the incident to the police. The collaboration between the public and law enforcement, facilitated through criminal reporting mechanisms, proves crucial in furnishing timely and accurate information essential for identifying and apprehending perpetrators (Reisig & Parks, 2000). This collaboration underscores the importance of a cooperative relationship between law enforcement and the community in maintaining public safety.

Crimes manifest across a spectrum of severity, necessitating varied responses within the criminal justice framework (FBI, 2019). When police receive a report of suspicious or illegal activity, they will issue a response typically involving one or two police officers that will arrive at the reported location to gather information, deescalate disputes, and for more serious offenses, collect evidence to establish probable cause . This evidence may lead to the arrest of a suspect or the issuance of a warrant request by a judge, allowing access to property for crucial evidence gathering to facilitate an arrest. In cases where a criminal act is directly witnessed by an officer, they confront the individuals involved, inform them about the illegality of their actions, and decide whether to proceed with arrests of any suspects. This process highlights the importance of police responsiveness and discretion in addressing a wide range of criminal activities.

The initial investigation process that unfolds prior to making any arrest varies widely in duration. The mere observation of a crime by an officer is often sufficient evidence to establish probable cause for an arrest. However, in other situations, investigations extend over years or even decades before resulting in an arrest. For instance, nearly two decades of investigations transpired that led to the apprehension and sentencing of the “Green River Killer,” Gary Ridgway, a notorious serial killer in Washington State during the early 1980s to the late 1990s (Keppel & Birnes, 1995), pictured in Figure 1.9. In contrast, certain cases, such as the mysterious DB Cooper case, remain unsolved, and after an extended period, become cold cases with no resolution. This disparity of investigation timeframes edifies the complexity of investigations and the persistence required to properly address each unique criminal case.

Figure 1.9

1.5.2 Arrest

Once probable cause has been established, officers have the authority to arrest a suspect and take them into custody, restricting their individual freedoms, including the right to depart. Once under arrest, the suspect is officially under the control of the officer, yet maintains some constitutional protections as indicated by the Miranda Rights (Miranda v. Arizona, 1966), which must be recited by an officer only after an arrest has been made and prior to further questioning.

Figure 1.10

Law Enforcement Officer Detaining a Suspect

1.5.3 Booking

Once the suspect is arrested, they are taken to the police station, jail, or detention center for booking, which is a standard protocol in the criminal justice system designed to establish a formal record of the arrest, including the suspect’s personal information, identity, fingerprints, and mugshot. A thorough search of the suspect is also conducted, involving the removal of any personal items. In general, booking is a critical juncture crucial for determining if the suspect will be further processed by the criminal justice system. In some situations, bail for the suspect may be set during the booking process. Bail is based on an initial determination of the amount required for the suspect’s release pending further legal proceedings. This comprehensive procedure ensures timely documentation of the arrest record and initiates the formal legal proceedings against the accused.

1.5.4 Custody

While the suspect is detained, law enforcement may continue their investigation to gather additional evidence. Officers may conduct interrogations in an attempt to elicit a confession to the crime by the suspect as well as gain insights into the motives behind the alleged crime. In some cases, officers may also organize in-person or photo lineups to identify potential witnesses or further connect the suspect to the crime. The imperative to find additional evidence is heightened as law enforcement typically have a 48-hour window to detain the suspect and demonstrate probable cause to advance the case to the prosecutor (Mulroy, 2012). If, for any reason, the prosecutor believes probable cause was not established within this timeframe, they must release the suspect. This critical period underscores the efficient and thorough investigative procedures to ensure the lawful and just processing of individuals in custody.

1.5.5 Charging

Once the arresting officers believe they have gathered sufficient evidence, they allocate the case to the prosecutor’s office. The prosecutor undertakes a comprehensive review of the case to determine the appropriate charges to bring against the suspect, taking into consideration various factors. These factors include the severity of the crime, the quality of the evidence, potential political or social pressures, and the likelihood of the court finding the suspect guilty. Subsequently, the prosecutor has three primary options: 1) return the case to law enforcement for further investigation, 2) decline the case, a decision known as nolle prosequi , or 3) proceed to file the case in court and begin the process of officially charging the suspect of a crime. This pivotal stage in the legal process highlights the discretion and responsibility vested in prosecutors as they make crucial decisions that significantly impact the trajectory of a criminal case.

1.5.6 Preliminary Hearing

Under the U.S. Constitution, the government, represented by the prosecutor, must demonstrate probable cause that the accused has committed the alleged crimes as indicated in the charges. In all but two states, a grand jury is employed to varying extents to assess whether the prosecution has presented sufficient evidence to proceed with the case. If the prosecutor successfully provides ample evidence, the grand jury issues a true bill of indictment , specifying the exact charges and officially charging the suspect, who then becomes the accused. In jurisdictions that do not utilize a grand jury, the prosecutor directly files charging documents with a judge. Subsequently, a preliminary hearing is scheduled, during which the prosecutor presents the merit of the evidence before a judge. Simultaneously, the defendant and defense attorney have the opportunity to challenge the prosecutor’s charges. In this process, the judge, rather than a grand jury, determines whether the evidence is substantial enough to warrant proceeding to trial. This legal procedure ensures a careful evaluation of the evidence before the case advances in the criminal justice system.

1.5.7 Arraignment

An arraignment is often scheduled after the judge or grand jury rules in favor of the prosecutor in the preliminary hearing. During the arraignment, the defendant is formally notified of the charges brought against them and is required to submit an official plea of not guilty , guilty , or no contest . Simply stated, a not guilty plea affords defendants the opportunity to formally contest the charges in court or begin the process of negotiations for a plea deal. A guilty plea, however, is an admission of guilt to the charges and allegations and leads to sentencing, which may occur immediately or transpire at a later time. On the other hand, a no contest plea allows a defendant to accept the conviction and charges without admitting guilt and is followed by sentencing that is either given immediately or at a future date. Although both a guilty plea and a no contest plea agree to the conviction and acceptance of punishment for a committed crime, a no contest plea does not admit guilt and can not be used as evidence in civil court, whereas a guilty plea can be used as evidence in civil courts. This critical stage in the legal process provides the defendant with important choices that shape the direction of the case as it is processed through the criminal justice system.

Figure 1.11

1.5.8 Bail Hearing

If bail was not set during booking, a separate bail hearing will be held to determine if the defendant can be released from jail before trial. While all defendants have the right to a bail hearing, not all defendants will be released on bail. For less serious charges and when the defendant is neither a flight risk nor poses a risk to others, they might be released on recognizance . However, for more serious charges, the judge will consider multiple variables, including the past criminal record of the accused, flight risk, and social network, to decide whether to grant bail and determine the appropriate bail amount. If the defendant possesses the financial resources to post bail, they will be released pending the final case verdict. When released on bail or on recognizance, judges often impose conditions that the defendant must follow. In cases where the defendant is denied bail or cannot afford it, they are housed in jail to await their trial.

1.5.9 Plea Bargaining

Plea bargaining is a process in which the defense and prosecution engage in discussions regarding a potential guilty plea in exchange for various forms of leniency, such as a reduction in the number of charges, a decrease in the severity of the charge, or a more lenient sentence (Bibas, 2004). Plea bargaining can take place at any point in the legal proceedings after arraignment and before the conclusion of the trial.

Ethical Dilemma in Criminal Justice: Plea Bargaining

Plea bargaining is a crucial component of the criminal justice system that benefits the defendant, courts, and taxpayers. Despite its positive intentions, however, this practice introduces a range of ethical dilemmas that warrant careful consideration. One primary concern is the potential coercion of a defendant who, despite their innocence, may accept a plea deal due to a strong interest to avoid uncertainties and potential harsh trial verdicts. This raises significant ethical questions pertaining to the protection of individual rights during the legal process as well as the overall fairness that result in the criminal justice procedure. In addition, plea bargaining has undergone criticism for its contribution to systemic inequalities, particularly among defendants with limited economic resources and lack of information about their rights. The expediency of plea bargaining also carries the risk of compromising the pursuit of justice by discouraging thorough investigations and hindering the presentation of all relevant evidence. Striking a balance between the efficiency benefits of plea bargaining and the imperative to uphold ethical standards remains a complex challenge in the criminal justice system.

1.5.10 Adjudication

If the prosecution and defendant fail to reach an agreement on a plea of guilt, the case proceeds to a criminal trial where either a jury or judge (known as a bench trial ) will determine whether the prosecutor can prove, beyond a reasonable doubt, that the defendant is guilty of the charges. The trial follows a structured process, allowing both the prosecution and defense to present their cases. The jury trial can yield a guilty verdict, a not guilty verdict, or a hung jury. After a guilty verdict, the defendant is scheduled for sentencing, whereas after a not guilty verdict, the defendant is released from custody and free to go. When the jury is unable to agree on a verdict, they are considered deadlocked or a hung jury. In such instances, the case remains unsolved, and the prosecutor must decide whether to drop the case or request a retrial at a later date.

1.5.11 Sentencing and Punishment

Once the defendant is found guilty in court or enters a guilty plea, they proceed to the sentencing phase for punishment. Punishments vary widely and can range from a small fine to life in prison, or even the death penalty (Bibas, 2004). The judge will often rely on pre-sentencing reports developed by community correction officers, the defendant’s previous criminal record, the seriousness of the crime, and other relevant variables to aid in the determination of the exact nature and length of the sentence of the state authorized punishment.

Figure 1.12

1.5.12 Corrections

Once the offender is sentenced, they are placed under the authority of the local, state or federal corrections departments. An offender may be placed on probation, in a community corrections facility, rehabilitation center, jail, or prison (Bibas, 2004). Offenders placed in jail or prison may have the opportunity to participate in rehabilitation, workforce, and education programs, depending on the available offerings at the corrections facility. Following the successful completion of a jail or prison sentence, ex-offenders are released into society, typically under some form of parole or community corrections supervision.

Figure 1.13

1.5.13 Community Corrections

While prison and jail are commonly associated with corrections, it is essential to recognize that a significant portion of individuals under the jurisdiction of corrections departments are within the community corrections system. Community corrections serve either as an alternative punishment to incarceration (e.g. community service, probation, house arrest) or as a post-release supervision process designed to assist ex-offenders to reintegrate into society while providing oversight to protect the community (Bibas, 2004). Individuals in the community corrections system are not entirely free, as they may be subject to drug tests, random house searches, or the loss of various privileges, such as voting rights, driver’s licenses, and gun ownership.

Review Checks