7.4 The Professional Era

The shortcomings in policing during the political era led to external civilian pressure for reform, giving rise to the reform or professional era of American policing in the early 1900s, persisting through the early 1960s. By the late 1920s, the close entanglement of policing with local politicians and business leaders, determined to utilize police for personal political gain and illicit profit, compromised effective strategies, fostering corruption within individual officers and entire departments (Reiss, 1992). This widespread issue, coupled with unprofessional conduct, became untenable, prompting internal and external calls for police reform by the late 1930s.

After the turn of the century, social pressures perpetuating professional police reform efforts instigated additional discussion concerning the precise roles, functions, and responsibility of law enforcement, as well as general departmental structure and operations.

The idea that the police should do more than just arrest criminals, that they should seek to prevent crime and rehabilitate offenders had been suggested years before. But it was not until after the turn of the century, when it enjoyed the support of similar reforms in other areas of American life, that it gained acceptance within police circles. (Walker, 1977, pp. 53-54)

Due to varying interpretations and emphasis on different aspects of professionalization, a broad swath of new reform policies were introduced that, in some instances, substantially differed across departments.

7.4.1 Early Reform (1920-1930)

During the 1920s and 1930s, many police departments narrowed their functions to focus on criminal investigation, suspect apprehension, and crime control (Kelling & Moore, 1988). Professionalization manifested differently in this approach, allowing certain officers to specialize in specific areas of policing rather than only work patrol, concurrently reducing opportunities for corruption by local politicians and community members.

Technological advancements in the early 20th century, such as the automobile, two-way radio, and telephone, made this approach feasible. The adoption of automobiles enabled officers to substantially increase area coverage and respond to emergencies more quickly. Innovations like the two-way radio and telephone significantly increased communication. For the first time, commanding officers could maintain continuous contact with patrolling officers through the two-way radio, and the telephone provided citizens with an opportunity to immediately connect with the police.

Figure 7.8

Leaders such as police chiefs August Vollmer, O.W. Wilson, and Richard Sylvester emerged as important advocates for a more professional police force through endorsements of higher education, modern technology, and elevated standards of professionalism (Uchida, 2005; Walker, 1977). However, the first challenge was addressing corruption and political influence in police departments. Departments implemented civil service systems that emphasized crime prevention and scientifically-based investigation techniques, simultaneously curbing political interference in hiring practices. Many states eliminated patronage hiring practices of police chiefs, adopting civil service examinations or allowing police commissions to appoint chiefs to lifetime tenure (Kelling & Moore, 1988). Changing the hiring practices of police chiefs was not the only adjustment made to avoid corruption. For instance, in Philadelphia, it became illegal for an officer to reside in the same neighborhood where they worked, and officers were limited to patrolling the same beat . Additionally, during this time, training academies were established to enhance officer expertise.

7.4.1.1 August Vollmer

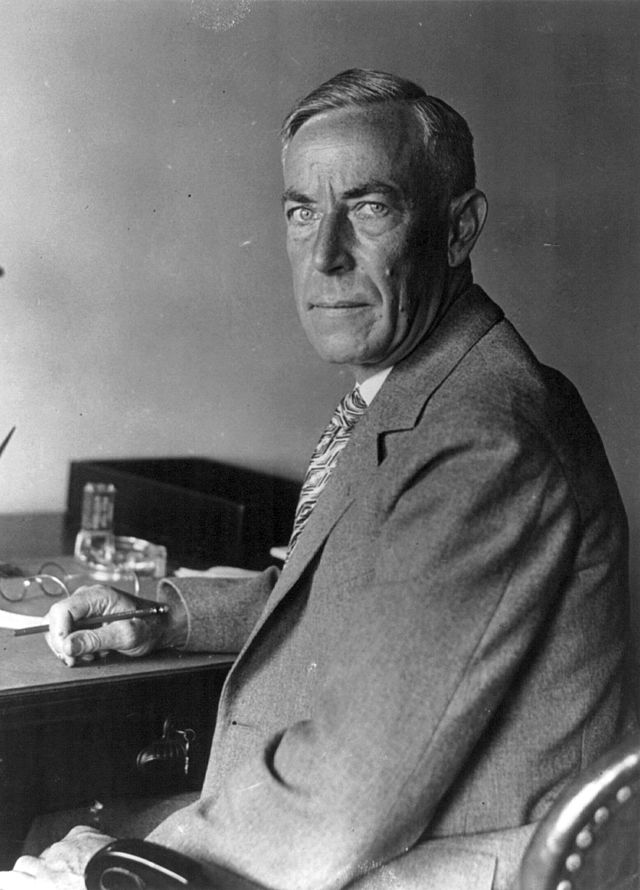

Figure 7.9

August Vollmer, often revered as the “Father of Modern American Policing,” played a pivotal role in the professional policing era in America during the early 20th century (Oliver, 2017). Born in 1876, Vollmer’s law enforcement career began in the late 19th century after military service in the Philippines during the Spanish-American War (Wilson, 1953). Following a successful four-year term as Barkeley’s elected marshal in California, Vollmer was appointed as the first Police Chief of the Berkeley Police Department in 1916, setting a standard for police departments across the nation until his retirement in 1932 (Douthit, 1975).

Vollmer’s leadership in law enforcement was categorized by an unwavering commitment to improving training and professional standards for officers. His progressive reforms reflected the social movement towards professionalization of law enforcement, addressing public concerns about the inadequate police response to rising crime (Walker & Boehm, 1997). In the aftermath of an era marked by widespread police brutality and corruption , Vollmer implemented mandatory police training classes, advocated for hiring of college-educated officers, and was among the first to hire Black officers in 1919 and female officers in 1925, challenging discriminatory employment practices prevalent at the time (Kell, 2017).

Impactful Moments in Criminal Justice: More Inclusive Police Employment Practices

The police reform era marked significant policy shifts, forever changing the employment landscape in American law enforcement. Before this era, women were excluded from employment in law enforcement, and Black men were either excluded or relegated to limited roles. The era’s focus on standardized procedures and less discriminatory hiring policies not only enabled the entry of women into law enforcement but also expanded opportunities for Black officers, representing a pivotal milestone for social equality and establishing essential foundations for subsequent equal rights movements among women and African Americans.

In conjunction with police professionalization reform efforts, civil service hiring procedures were implemented, emphasizing education, temperament, and adherence to standardized procedures. This shift allowed for the employment of the first female officer in 1905 (Walker, 1977). Prior to this milestone, female participation in law enforcement was extremely limited. In contrast to male officers during the early 20th century, who often came from poor families and had minimal education, policewomen during this time were from middle and upper-class families and were often college-educated. Despite this significant education discrepancy, opportunities for policewomen remained exceedingly limited, highlighting the numerous obstacles and challenges faced by women in a society entrenched in structural gender bias and overt sexism .

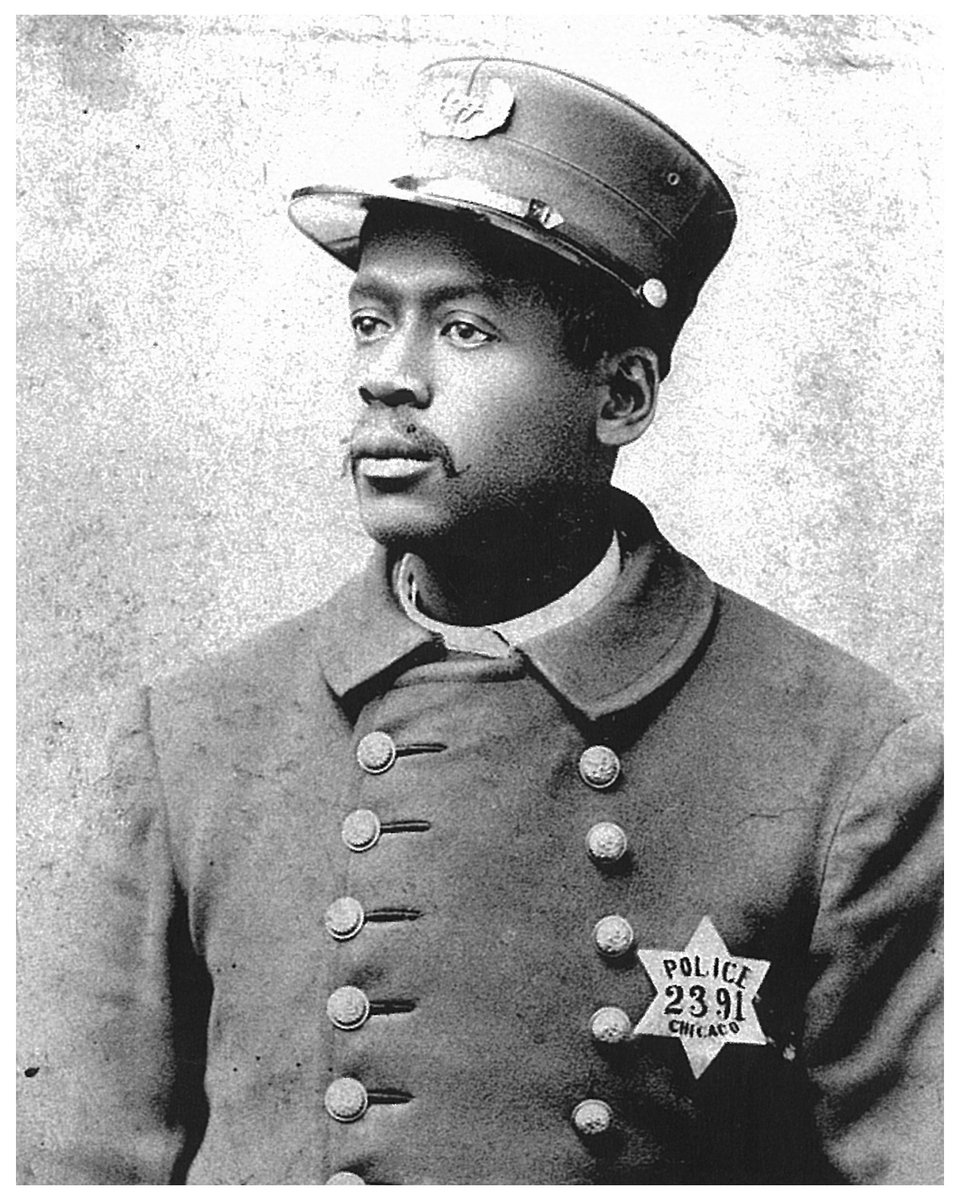

Figure 7.10

Evidence of limitations for policewomen were apparent by the shortlist of roles and responsibilities, and little opportunity for career advancements. During the reform era, policewomen were mainly utilized for social work-related duties, such as working with juveniles and female victims of crime, as well as undercover operations, typically posing as prostitutes or female citizens to gather information for vice crimes . After World War II, some police departments allowed policewomen to partake in “normal” police tasks more aligned with the duties of their male colleagues. Despite these rare occurrences, limited opportunities existed for women in law enforcement outside of social work during this time (Walker, 1977). Nevertheless, the inclusion of women in law enforcement marked a significant departure from the previously male-dominated field. Granting women official roles of authority in society was paramount for propelling efforts towards equal opportunities and overcoming structural sexism barriers, which, despite efforts for women’s social equality, remains a critical issue in modern society.

Figure 7.11

The reform era also perpetuated positive change for Black policemen, expanding their roles and opportunities beyond the narrow range of duties that typically consisted of undesirable jobs, such as janitorial work (Kuykendall & Burns, 1980). Records indicate a small number of appointed Black police officers during the political era, at the end of the 19th century, with possibly the first Black officer being appointed in 1867 in Salem, Alabama followed by Jackson, Florida in 1868 (Dulaney, 1996). The north began appointing black officers in Chicago, Illinois in 1872 followed by Philadelphia, Pennsylvania introducing their first Black officers in 1884 with an appointment of 35 Black officers (p. 20). This was met with considerable opposition and even erupted in instances of them being accosted in the streets by racist whites but, over time, they were eventually accepted as normal components of the system. Black policemen during the late 19th century “worked in plain clothes—in part not to offend the sensibilities of racist whites” (Walker, 1977, p. 10) and were only allowed to patrol Black neighborhoods with no jurisdictional authority over whites. Policy changes brought about during the reform era helped erode these limitations, expanding the authoritative duties of Black policemen; however, most changes were slow to take hold on the national scale, and many challenges stemming from racial bias , which persisted despite these crucial steps towards greater racial diversity in American policing. Nevertheless, the inclusion of Black policemen in law enforcement was critical for challenging stereotypes and providing Black men the opportunity to have roles of authority in society.

The reform era brought about a transformative shift in American policing, marking significant achievements for inclusivity and social diversity efforts; although these improvements only affected white women and Black men and excluded Black women and all other minority groups. Despite persistent challenges for policewomen and Black policemen during this time, these changes to police employment practices indicate an important departure from historical exclusionary practices in law enforcement. Beyond laying the foundation for more diverse and inclusive American police forces, the policy changes during the reform era established essential groundwork for social equality movements in the ensuing decades.

Vollmer’s contributions to the professionalization of policing were vast. One key initiative was the establishment of the first policing school in the United States (Oliver, 2017). The Berkeley Police School, founded in 1906, evolved into the Berkeley Police Department. This institution, departing from the traditional apprenticeship approach, introduced a systematic and academic approach to law enforcement education. Officers received training in crime investigation, legal procedures, and community relations, establishing a framework for a more informed and skilled police force (Douthit, 1975).

Scientific methods in crime detection were a hallmark of Vollmer’s contributions. Recognizing the need for a systematic and efficient strategy to solve crimes, he integrated scientific principles into policing. A firm believer in the science of police work, he introduced technologies like the lie detector and crime lab forensic science. Vollmer emphasized forensic techniques, such as fingerprint analysis and ballistics, enhancing the accuracy of criminal investigations (Kell, 2017). This emphasis not only improved law enforcement effectiveness but also laid the foundation for modern forensic practices (Douthit, 1975).

Additionally, Vollmer played a crucial role in standardizing police practices. Importantly, he advocated for the development of uniform crime reporting methods and record-keeping systems that cultivated a consistent and reliable database for analyzing crime trends. This commitment to data-driven decision-making enabled police agencies to effectively allocate resources and address emerging challenges, which became a cornerstone of modern law enforcement strategies (Douthit, 1975).

The adoption of motorized patrols was another significant innovation introduced by Vollmer. In a time dominated by foot and horse patrols, Vollmer recognized the potential to revolutionize police mobility through the integration of newly emerging travel technologies. Equipping officers with bicycles in 1910, motorcycles in 1911 (National Motorcycle Museum, 2018), and patrol cars in 1914 all enhanced crime prevention and response, while symbolizing a crucial departure from the archaic image of the static, foot-patrolling officer (Oliver, 2017). In addition to these achievements, Vollmer is also credited as the first police chief to equip patrol cars with two-way radios in 1929 (Douthit, 1975), further improving police communication and response.

Vollmer’s vision for policing was truly groundbreaking. His innovative approach prioritized active officer engagement with the communities they served, fostering a newfound cooperation and trust between citizens and local law enforcement officials. He underscored the importance of a holistic policing strategy that considered underlying social conditions as contributing factors influencing crime (Oliver, 2017). Vollmer advocated for an understanding of these factors among police officials, which was paramount to the later development of a preventative approach to law enforcement.

The significance of Vollmer’s policing philosophy laid the groundwork for future efforts to bridge the gap between police and the public. This challenge for law enforcement reemerges over time, especially amid cultural changes and the expanding demands of a growing, pluralistic, democratic society (Douthit, 1975). Nevertheless, Vollmer’s ideas have proven to be pivotal in shaping the trajectory of law enforcement, emphasizing the need for a collaborative and proactive approach to policing that takes into account the broader social context.

Vollmer’s steadfast commitment to professionalism and innovation earned him widespread recognition, propelling his rapid ascent to prominence and exerting a profound, positive influence on policing practices at the national scale (Bopp, 1977). Orlando W. Wilson, a distinguished scholar of American policing, encapsulated August Vollmer’s career with the following words:

From the beginning Vollmer’s police career was marked, first, by a stubborn insistence that any task could be accomplished and any problem solved if he thought about it and worked at it long and hard enough, and second, by an ingenuity and resourcefulness that enabled him to develop unique methods to accomplish his purpose. His clear vision and critical mind enabled him to probe quickly to the core of any problem. His fresh approach and unswerving determination brought solutions that all too frequently were met by derision from his colleagues, the press, and the public. In consequence, hundreds of experienced police officials scorned, at first, the ideas developed by this young man from a small Western town. But the police profession today recognizes that Vollmer was right in his proposals; his procedures have been adopted by progressive police departments throughout this country as well as abroad. (1953, p. 97)

Chief Vollmer stands out as a prime example of police administration leadership that played a pivotal role in the crucial reformation of policing during the professional era (Oliver, 2017). Through his unwavering emphasis on education, application of scientific methods, standardization of police practices, implementation of an active, community-engaged policing approach, and the integration of technological innovation, Vollmer not only reshaped law enforcement but also set a new paradigm for the field.

His enduring legacy continues to wield a profound influence on modern policing, serving as a reminder of the paramount importance of adaptability, professionalism, and community collaboration among law enforcement in their relentless pursuit of public order and safety (Oliver, 2017).

7.4.1.2 Wickersham Commission

By the late 1920s, burgeoning public interest and controversy surrounding reform of criminal justice institutions had taken root nationwide. In response to these escalating concerns, President Herbert Hoover’s administration established the Wickersham Commission , officially known as the National Commission on Law Observance and Enforcement, in 1929. This commission was tasked with conducting an extensive evaluation of American social institutions, later recognized as the criminal justice system . Named after its chairman, George W. Wickersham, a distinguished attorney and former U.S. Attorney General, the commission’s work was exhaustive and comprehensive, spanning a wide range of issues spanning beyond the three major branches of the criminal justice system (law enforcement, policing, and courts), including criminology, crime statistics, and costs of crime (Walker & Boehm, 1997) .

The commission’s multifaceted investigation included an examination of the legal landscape, focusing on the effectiveness of Prohibition, widespread citizen violations of Prohibition, and the strain on law enforcement stemming from the nationwide ban on alcoholic beverages. Beyond Prohibition, the commission delved into law enforcement practices, addressing issues such as corruption, brutality, and the use of excessive force within law enforcement agencies, harshly condemning many observed policing practices (Walker, 1977). It also scrutinized criminal procedure, aiming to ensure fairness and due process in law enforcement. Additionally, the Wickersham Commission explored the conditions and treatment of individuals in penal institutions, contributing to discussions about criminal punishment and rehabilitation (Walker & Boehm, 1997).

Figure 7.12

The comprehensive findings of the commission, primarily authored by August Vollmer, were documented in a series of reports issued between 1931 and 1932, collectively known as the Wickersham Commission Reports. However, due to the Stock Market Crash in 1929 and the subsequent economic downturn, the country’s focus shifted almost entirely towards economic recovery efforts by the time of the Wickersham Reports’ release. This shift in focus negatively influenced the effectiveness of the committee’s efforts, and as a result, the Wickersham Report “had little immediate impact on public policy” (Walker & Boehm, 1997, p. vii).

One pivotal segment of the commission’s findings that yielded significant and immediate socio-political influence was the Report on Lawlessness in Law Enforcement (Walker, 1997). This comprehensive report meticulously detailed observations and evidence gathered from fifteen cities across the country, exposing prevalent illegal, improper, and unethical law enforcement practices. These practices encompassed the use of threats and intimidation tactics, physical torture, denial of legal counsel, illegal detention, and unreasonably protracted questioning of suspects in custody (Calder, 1993).

The reports provided a thorough analysis of the American criminal justice system at the time, accompanied by a plethora of recommendations for reform (Walker & Boehm, 1997). While not all proposed recommendations found immediate implementation, the commission’s work established a vital foundation for ongoing discourse surrounding American criminal justice system reform in the ensuing decades. This influence resonated, shaping the trajectory of these systems (Walker, 1997) as well as the study of criminology (Walker & Boehm, 1997) in subsequent decades.

7.4.1.3 Senate’s Crime Committee (Kefauver Committee)

By the late 1940s, organized crime stories dominated the newsstands, revealing a government plagued by extensive corruption and the influence of organized crime syndicates in major cities across the country (U.S. Senate, 1950-1951). By the decade’s end, concerns about corruption and unethical behavior, especially within law enforcement, had escalated, sparking discussion among elected officials in various political circles (Boston Public Library, 2024). These conversations revolved around finding appropriate response to numerous requests for federal assistance to address organized crime, particularly its infiltration into interstate commerce , and the economic threats posed by labor racketeering .

To tackle these concerns, the Senate’s Crime Committee, officially known as the Senate Special Committee to Investigate Organized Crime in Interstate Commerce, was established in 1950. Commonly referred to as the Kefauver Committee after its chairman, Senator Estes Kefauver, this committee was tasked with investigating and addressing organized crime activities affecting interstate commerce (U.S. Senate, 1950-1951).

Over the following 15-month period, the committee conducted investigations into widespread police corruption by organized crime syndicates. It televised over a dozen hearings, presenting crucial evidence and featuring more than 600 witnesses. These hearings generated significant interest among millions of American viewers, who witnessed the testimonies of former mafia members such as Mobster Frank Costello, pictured in Figure 7.13 (U.S. Senate, 1950-1951). The public became acutely aware of the powerful influence of organized crime syndicates, particularly the Mafia , on both politics and law enforcement through the publicity of these hearings (Boston Public Library, 2024).

Figure 7.13

The committee’s collaborative efforts yielded several positive outcomes. Firstly, it brought the pervasive influence of organized crime in the U.S. to the forefront of public awareness. FBI Director Hoover acknowledged the national scale of organized crime syndication and admitted the FBI’s failure to address the issue (Friedman, 2005). Additionally, the committee spotlighted organized crime’s involvement in the gambling industry, leading to the dissolution of legislative proposals and state ballots referendums concerning gambling legalization. While immediate legislative changes did not transpire, the Kefauver Committee recommended the expansion of civil law to combat organized crime, a recommendation Congress fulfilled in 1970 with the passing of the Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations Act (RICO).

Crucially, the committee’s collective efforts ignited future government actions against organized crime, leading to the creation of over 70 “crime commissions” at the state and local levels. For these reasons, the Kefauver Committee is widely viewed as a pivotal milestone in the federal government’s fight against organized crime.

Review Checks

7.4.2 Later Reform Era (1930s-1960s)

Between the 1930s and 1960s, the growing prevalence of automobiles led to increased demands for traffic control, as well as reduced face-to-face interactions of patrolling officers and the public due to the reduced time spent traveling streets by foot. Reinforced by the narrowing of police responsibilities, reduced officer interaction with the public, internal and external department support for professionalization police reform, and findings from the Wickersham Commission, police agencies shifted their focus from social services to crime control (Walker, 1977).

Reform efforts centering on the separation of law enforcement from political leadership were successful. Consequently, this social distancing extended beyond local politics, resulting in an equal distancing of police departments with the local community they served. Over the ensuing decades, this separation transformed police departments into entities focused solely on crime fighting. However, this detachment from local communities left them lacking the necessary skills and experience to handle political unrest effectively and ethically in communities, resulting in brute suppression of people that challenged police authority.

7.4.2.1 The Tumultuous 1960s

Social turbulence began to take shape in the early 1960s, introducing a series of new obstacles for the police. During this time, illegal drug use gained prominence as the overall crime rate began increasing (Blumstein & Wallman, 2000). In addition to growing anti-war sentiment and civil rights movements, these factors imposed major challenges on the police’s efforts to maintain a public image characterized as equitable, successful crime fighters, and upholders of social order.

7.4.2.1.1 Social Unrest, Protests, and Riots

By the early 1960s, police officials, as representatives of the government-authorized enforcers of law, became synonymous with symbols of racism , inequality , and social injustice perpetuated by the high number police brutality incidents that included frequent beatings, abuse, and unjustified killings of Black Americans. Tension and grievance related to police brutality and discriminatory practices, in addition to longstanding racial and economic disparities sparked largescale protests and violent riots in major metropolitan cities across the U.S.

Among the dozens of protests that transpired throughout this troubling era of social unrest was the Harlem Riot of 1964, often referred to as the Harlem Uprising, in the Harlem neighborhood of New York City. According to official reports, the protest was ignited by the police shooting of a 15-year-old African American boy by a white, off-duty police lieutenant following a confrontation, although the exact circumstances that led to the shooting were disputed. News of the shooting rapidly spread, and tension escalated, leading to protest, demonstrations, and eventually, widespread violence over several days, resulting in 100 injuries, one death, 500 arrests, and extensive property damage (Hayes, 2021).

Months later, the 1965 Watts Riots, also known as the Watts Rebellion, occurred in the Watts neighborhood in Los Angeles, California, stemming from an altercation between a Black motorist and an officer of the Los Angeles Police Department (LAPD). During the arrest of the Black motorist, tensions escalated and quickly manifested into widespread violence, looting, and arson that lasted six days, as captured below in Figure 7.14. Law enforcement response was significant, with the California National Guard and the U.S. Army deployed to quell the unrest. By the time the violence subsided, there were over a thousand injuries, 34 officially reported deaths, and approximately 4,000 arrests (Burby, 1997).

Figure 7.14

Additionally important are the Detroit Riots, also known as the 12th Street Riot or the 1967 Detroit Rebellion, which occurred from July 23-27, 1967, at the peak of the civil rights movement. This event serves as a stark reminder of the deep-rooted systemic racism and social inequalities plaguing American history. The riot began as a civil disturbance in Detroit, Michigan, triggered by a violent police raid on an unlicensed bar in the early morning hours. Frustration and discontent, fueled by longstanding racial tensions and exacerbated by decades of systemic racism, discriminatory policies, and economic disparities within African American communities, led to five days of looting, arson, and vehement confrontations with law enforcement. The Michigan National Guard and the U.S. Army were eventually deployed to assist local law enforcement.

The aftermath of the Detroit Riot was profound, resulting in extensive property damage including the destruction of numerous homes and businesses as depicted in Figure 7.15 below. Over 1,000 injuries and 43 reported deaths occurred (Locke, 2017). However, early news reports significantly underestimated the magnitude of arrests, initially stating that only 48 individuals had been apprehended, while the true figure was much higher, nearing 7,000. This discrepancy underscores the chaotic and tumultuous nature of the riots. Additionally, the failure to accurately report the extent of arrests likely reflects a historical pattern of media bias and neglect toward issues affecting marginalized communities, highlighting the continuous need for unbiased, transparent, and accountable reporting in the pursuit of comprehensive coverage of current events (refer to the newspaper excerpt featuring captions and a photo depicting at least 30 prisoners, primarily Black, crowded into a small holding cell, for more on the inaccuracies in news reporting and racially motivated arrests.)

Figure 7.15

Not reported were the deplorable conditions faced by the individuals arrested during the riots. Due to sufficient space to hold the large number of arrested individuals, they were subjected to overcrowded holding cells and deplorable conditions that violated their basic human rights. With limited space, inadequate ventilation, and insufficient amenities, occupants in these conditions typically experienced great discomfort, heightened risk of illness, and mental anguish (Baffour et. al, 2024). The lack of access to proper sanitation facilities and medical attention often exacerbates the dire circumstances, leading to a distressing and potentially hazardous environment for those awaiting due process. This aspect of the riot’s aftermath highlights the broader systemic issues within the criminal justice system, emphasizing the need for reform and greater attention to human rights in times of crisis.

Despite efforts in the professional era to enhance law enforcement’s objectivity, expertise, and systematic approach, evident shortcomings persisted. In response and to better study the criminal justice system, President Johnson called for the creation of an Office of Law Enforcement Assistance and established the President’s Commission on Law Enforcement and Administration of Justice in 1965, ushering in a new era of policing and setting the stage for the evolution of modern police practices (Walker, 1977).

7.4.3 Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI)

In 1908, Attorney General Charles Bonaparte issued an executive order under President Theodore Roosevelt to assemble a cadre of special agents for the newly established Bureau of Investigation (BOI), a branch of the Department of Justice (DOJ) entrusted with federal law enforcement and investigations. By 1919, nearing the end of World War I, the DOJ and BOI were predominantly focused on monitoring and apprehending individuals suspected of anarchist, Bolshevik , socialist, or other radical political ideologies under the 1917 Espionage Act and the 1918 Immigration Act (Masse & Krouse, 2003). Although these anti-communism efforts initially garnered public approval, public support had substantially dwindled by the early 1920s (Theoharis, 1999).

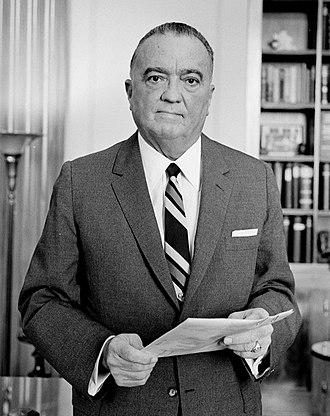

J. Edgar Hoover, pictured in Figure 7.16 below, strategically distanced himself from some of the more controversial anti-Red policies, greatly benefiting his career. In 1924, he was appointed as the Director of the BOI (later renamed the FBI in 1935), a position he held until his death in 1972 (Masse & Krouse, 2003). Under Hoover’s leadership, the agency underwent rapid transformation, implementing merit-based promotions to replace patronage and initiating major improvements to the agency’s public image. Hoover accomplished this by developing the “Public Enemies” list (later changed to the “10 Most Wanted”) and successfully pursuing notorious criminals such as Bonnie and Clyde, Al Capone, and John Dillinger (Masse & Krouse, 2003; Theoharis, 1999). Hoover played a paramount role in shaping the organization’s identity and operations, including renaming the agency to the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) in 1935.

Figure 7.16

The FBI , in collaboration with the International Association of Chiefs of Police (IACP) and the National Sheriffs’ Association (NSA), adopted the Uniform Crime Report (UCR) program in 1930. Ran by the FBI, the UCR was a centralized crime reporting program that standardized crime data for police departments to voluntarily submit local reported crime and arrest data. For over 90 years, the UCR played a pivotal role in enhancing our comprehension of criminal behavior. The UCR stood as the primary crime database in the U.S. until it was officially replaced by the National Incident-Based Reporting System (NIBRS) in 2021 (Christman & Piquero, 2022).

In the late 1930s, the FBI shifted its focus to domestic security, honing in on fascist and Communist organizations amid the political unrest erupting in Europe (Masse & Krouse, 2003). During WWII, the FBI assumed a pivotal role in investigating espionage, further solidifying its notoriety. In the subsequent Cold War era, the FBI redirected its attention to domestic security, with a particular emphasis on military spies and potential Russian assets, a focus that persisted until the collapse of the USSR in 1991 (Theoharis, 1999).

At the zenith of the Civil Rights Movement in the 1960s, the FBI gained heightened prominence through its investigations into civil rights violations and involvement in high-profile cases such as the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Throughout the 1960s and 1970s, the FBI undertook investigations related to the Mafia , aiming to dismantle major organized crime syndicates. In the 1980s and 1990s, the FBI expanded its intelligence presence, making a substantial impact on an international scale, particularly in the Middle East, with an emphasis on preventing future terrorist attacks such as the bombing of the World Trade Center in 1993 (Masse & Krouse, 2003).

Over the years, the FBI has evolved to address emerging threats, characterized by a dual mission: upholding and enforcing federal laws while protecting U.S. national security against terrorist and intelligence threats (Masse & Krouse, 2003). As the leading agency in the DOJ with a mandate encompassing both law enforcement and intelligence functions, the FBI remains a critical component of the U.S. government’s efforts to ensure public safety and national security.

7.4.4 Strengths and Shortcomings of Reform Era Policing Strategy

Several important advances in policing transpired during the reform era, as outlined in the list below. Most notably, professionalization of law enforcement, integration of technology, use of scientific methods, and standardization of police procedure, along with significant administrative changes characterized by reliance on lawful policies instead of political influence, greatly reduced corruption (Kelling & Moore, 1988; Uchida, 2005; Walker, 1977).

The professionalization of law enforcement officials made notable improvements through the implementation of civil service hiring procedures emphasizing the selection of educated individuals with the proper background and temperament and dedication of adherence to standardized police procedures (Kelling & Moore, 1988). Besides enhancing the quality of officers and building a more competent and disciplined law enforcement workforce, these employment practices also corresponded with newly implemented hiring policies that reduced recrimination, providing opportunity for the employment of the first female officers. Additionally, the introduction of effective training programs furthered professionalization efforts.

Organizational Strategies During the Reform Era (as cited in Kelling & Moore, 1988):

- Authorization: Law and professionalism.

- Function: Crime control.

- Organizational Design: Centralized, classical.

- Relationship to Environment: Professionally remote.

- Demand: Channeled through central dispatching activities.

- Tactics & Technology: Preventive patrol and rapid response to service calls.

- Outcome: Crime control.

Additional notable contributions this era was the implementation of technological innovation and scientific investigation methods. While technological innovation like automobiles and two-way radios substantially improved police response time and communication, the utilization of science-based investigation methods such as fingerprinting, lie detectors, and crime laboratories greatly improved outcomes. Moreover, the implementation of standardized investigation procedures, documentation, and strategic use of the Uniform Crime Report to measure crime and policing effectiveness were also significant achievements that mark this era.

Despite these positive changes, the end of the reform era is characterized by substantial shortcomings concerning resistance to reform, persisting discriminatory practices, and erosion of community relations furthered by isolative policing strategies and focus on crime control (Kelling & Moore, 1988).

Despite reform efforts, some police departments resisted reform and maintained traditional, often outdated, law enforcement practices, hampering opportunities for advancement. Of great concern was the resistance to reform specific to the implementation of less discriminatory policing practices. During this era, racial bias and discriminatory practices persisted in law enforcement, especially within departments and individual officers resistant to reform. Unfortunately, predominantly Black and minority communities continued to experience disproportionate instances of police targeting, harassment, and brutality.

Figure 7.17

Towards the end of the reform era, a realization emerged that the path of American policing again required radical correction. Administrative changes that isolated police departments from political influence had concurrently functioned to insulate them from informal community contact, furthering police isolation and eroding the relationship between law enforcement and local communities (Kelling & Moore, 1988). Furthermore, the integration of automobiles essentially eliminated the police officer walking the neighborhood beat; consequently, transforming law enforcement officials into faceless crime fighters hidden from view by the comfort and safety of their patrol cars. Additionally, the consequential restructuring of department command created animosity and conflict between patrol officers and administrators, heightened by widespread citizen and media critique. This, in conjunction with the adaptation of a narrowed focus on crime control that neglected the social factors underpinning criminal behavior, facilitated the development of a police subculture and perpetuation of an “Us vs. Them” mentality (Uchida, 2005).

The reform era of American policing, marked by monumental improvements, also faced considerable challenges. By the era’s conclusion, the police encountered significant criticism for blatant racial bias and discriminatory practices broadcasted by televised news media. Numerous instances of police using force against minority populations, particularly Black communities, were extensively documented. This negative portrayal, coupled with the rising crime rates in the 1960s and 1970s (Uchida, 2005), contributed to the deterioration of community relations with police, fostering widespread public mistrust and loud outcries demanding substantial changes to law enforcement practices.

Review Checks

Media Attributions

- CJ 6.